day 10

8 Nov, going to rain //

In my project for the university, I am trying to develop and argue for a new and improved way of accessing and experiencing lyric poetry (note I do not say ‘understanding,’ for this, I think, is a misaligned way of approaching the genre). I think of this ‘new’ theory as a contemplative practice of reading, one that involves thinking and feeling through lyric poems guided by the ideas and images of the mystical medieval German theologian Meister Eckhart. My logic for selecting one hugely popular German-language Modernist and one hugely popular American English Postmodernist follows that if this method of reading through Eckhart works with such widely-acknowledged and dissimilar poets as Rilke and Ashbery, this may show that the theory holds water, and may be applied to many other lyric poets, perhaps restricted to the Christian West, but perhaps not. I choose Eckhart because he is a giant figure in Western Christian mysticism and both Rilke and Ashbery wrote in Christian contexts (fin-de-siecle Europe and 20th-century US), regardless of their own personal religious inclinations. Further, the modernizing imposition of the secular onto their sociocultural contexts applied pressure to their vocation as poets, absorbing and reflecting their changing worlds.

von Hügel says that religion’s three expressions, which all rely on each other for balance and harmony, are institutionalism, intellectualism, and mysticism. I see a link between the subversive spirit of the modern lyric, especially in relation to institutions of education and publishing, and the subversive character of the mystical in medieval Germany. Many mystical thinkers of the Middle Ages were pillars of the institution; many were prosecuted and executed as heretics; these groups overlapped. Judaism and Islam had always taken for granted that their mystical elements involved esotericism—that there was salvific knowledge to be gained, but only by a secret, select few who could attain that pinnacle of understanding (aka gnosis). For Christianity, however, esotericism was always considered dangerous. I find it suggestive that Christendom, not able to tolerate the idea that certain language and practices afforded salvation without the aid of grace or divine mercy, persecuted its mystics as individuals and produced a modernity that neglects, impoverishes, and politically neutralizes its subversive artists. It is a popular commonplace to group poets and mystics together: they are both ‘of a community’ enough to be able to register its tendencies accurately, if idiosyncratically; and yet both also exist as outsiders because of their community’s struggle with grasping their messages.

Christian mystics between 1300 and 1700 tended to be labeled heretics: they were heard, investigated, and condemned. Rather than inquisition and burning—being made examples of—poets in the modern Christian West “make nothing happen,” to use Auden’s phrase: we are silenced by indifference, neglect, impoverishment; occasionally we are neutralized and fetishized as symbols for the use of the state, to underwrite its power (cf. the phenomenon of the poet laureate in the United States).

The language of late medieval mystical identity was one that was disturbing to the church for its violence and its individualism. To achieve union with God, to become that supreme power, required annihilation. Meister Eckhart and others around his time argued that in order to let the energy and action of God flow through you, your own soul must be annihilated to make way.

There are paradoxically optimistic moments of nihilism in poems of Rilke that make more ‘sense’ (poetic sense, if you will) when considered in terms of mystical annihilation of the soul. In a different but related way, the vacated seat of subjectivity whence issues the voice of many Ashbery poems becomes filled with a more present absence (again, if you will) when imagined to be the product of the process of a soul’s annihilation.

Perhaps Ashbery himself would not agree that he has deliberately emptied out his selfhood (as constructed by language in his poems) in order to invite some Christian divinity to occupy that seat!—but I am much less interested in the personal biographical opinions of individual poets than I am in sussing out, using a historical analogy or correlate from the Middle Ages, the complexly-layered relationship between the mystical thinker (i.e. the poet) and his societally-bound institutional setting (not the church, in our case, but the modernized ‘secular’ [and post-secular, but we’ll get to that in a later post] systems of the university (for any MFA holder, myself included), the New York art world (for Ashbery), and the French/Swiss/Bohemian bourgeoisie (for Rilke).

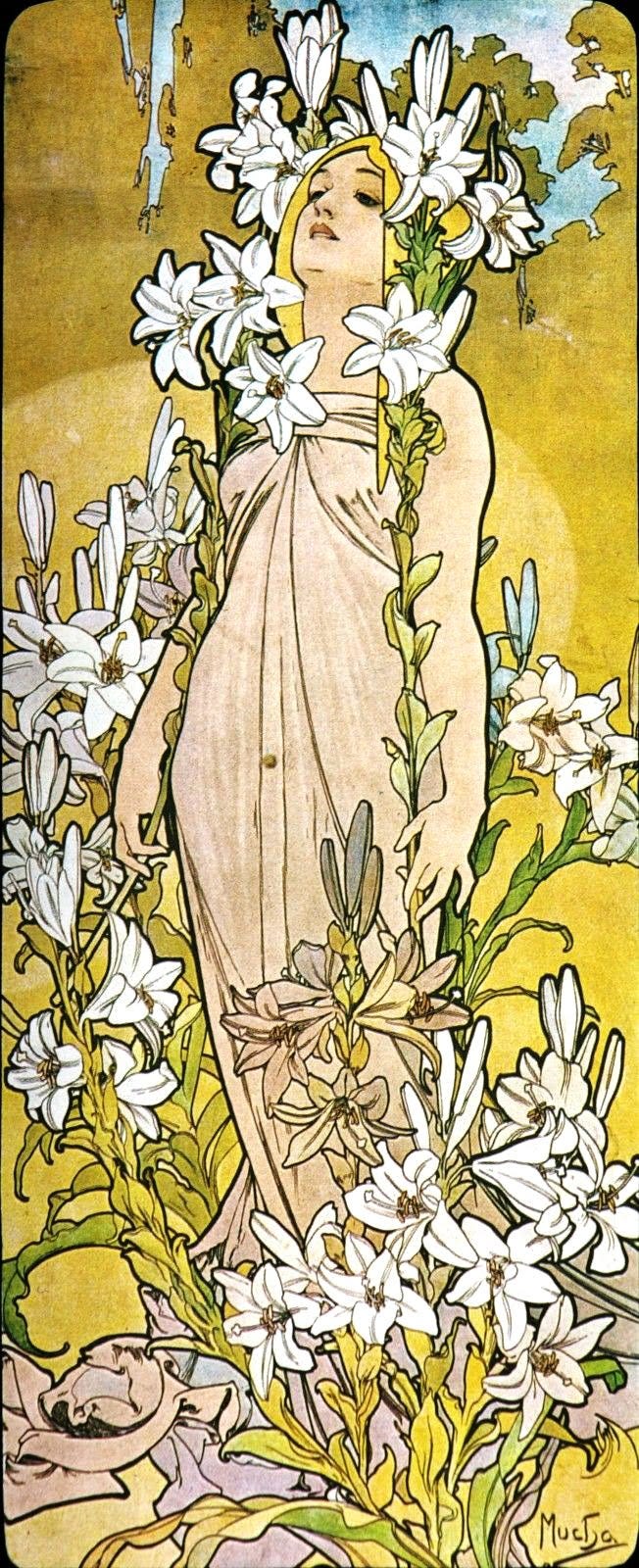

Image: Alphonse Mucha, 1898 (Prague)

Cf. Bernard McGinn, The Harvest of Mysticism in Medieval Germany. Crossroad, 2005.