If you are at home, you do not feel lonely:

on breathwork, birth trauma, labor strikes, & spiders in the desert

If you are at home, you do not feel lonely.

—Thich Nhat Hanh

*

Greetings—as promised, a longer piece on a matrix of ideas.

August 2021. J and I take the van out to Joshua Tree in late summer. We park on land that is communally owned by old hippies. We meet one in the pool carved out of rock where we soak all day. He is a chemist, and we talk about rocks, radiation, and crystals, and what makes up the stars and makes up us. He is a character who deserves his own book, so I won’t go too far with him here (tldr: ex-FDA master of conspiracy); suffice it to say, we visit his new trailer, where he offers us sacraments he has freshly synthesized.

We toast with glasses of chocolate milk and watch the sunset. We listen to our shaman talk about the logistical nightmare of being responsible for the electrical at Burning Man, and hear his plans for digging a well on this acreage overlooking what he calls Gamma Gulch. Shortly after J and I bid him adieu and drive Reggie back to our spot nestled in the hills. Night comes on. J puts music on and dances barefoot, unbothered. He has left the building, so to speak, and I know I am alone and unprotected. (There are no buildings for miles around, just fine sand, gamma-rich piles of rocks, and alien-looking Joshua Trees). I experience a crushing fear as I “come up” and fail to launch, as it were. Narcissistic aloneness. Terror. The horror is worse when my eyes are closed, but it does not matter: either way, shut or open, I see and am myself, and ‘I’ abhor her weakness, and resent her fear.

Seated in the front of the van, legs folded, I blink, and the movie starts. Sitting on my naked right thigh is an enormous spider, black, brown, and red; its abdomen and legs rest lightly but solidly, pressing into my flesh, and its ‘face’ looks up at me. I startle and begin my descent into hysteria.

I have always been arachnophobic. Tonight, each fear and each fleck of hatred manifests as a spider. Eyes open, eyes closed, they aren’t going anywhere. I cave in on myself, helpless and despairing. Enter the compassionless spideyverse. . .

The cacti, the rocks, the air in its stale waves, the stars in their brittle mapped shapes above, the grains of sand in their undifferentiated heaps below, the sheets of metal that form the body of the van: all are become spider. Spider is what is, in waves like water. Vivid experience of spiders as molecules of the universe and as making up each and every ‘thing,’ while also aware that nothing experienced in ‘normal life’ is any more or less real than this spidey version of the universe.

J sticks his head in the van to check on me at some point, and I recoil, screaming. He is the spider king, a massive specimen, bloodless, heartless, and brimming with poison. How disappointing. The most notable character throughout, or the most differentiated, is the large, simple spider on my right thigh—I stay paralyzed in the front seat of the van for hours, shuddering—that will not go away, just stares at me. Just is. Doesn’t even care about me, I realize now, if I had stopped to ask. Would that have helped?

I sleep through the last third of the trip, like an infant that falls unconscious when it’s afraid. Crawl into the back of the van to our bed and lay on top of the sheets, trying to breathe despite sensing another lake of legs bubbling beneath the blanket. Watch the spiders that lace the metal ceiling of the van like a raised sheet of poison doilies. Eventually my eyes close and they rush in through my mind to coat my eyelids, nostrils, gums, throat. . .

Wake up in the back of Reggie, J beside me, reverted back to (mostly) human. The spider storm has passed, as in, the night has gone; the sun is already high in the sky. J stirs. We drink water and put on cool sunscreen and music and dance in the sand. I am so relieved not to be afraid anymore.

*

This past summer, I attended a holotropic* breathwork group class at the Berkeley Alembic led by Loriel Starr, a sound healer (among other things) who studied with Stanislav Grof (*Loriel called her derivation holosonic). My interest in holotropic breathwork and my willingness to engage in it among strangers in a group setting (typically extreme turnoffs) had to do with the aforementioned experience.

In a way, I attended the session with the hope to counterbalance that bad trip. N.b., you aren’t supposed to say ‘bad’ in healing circles, you’re supposed to call shit ‘challenging’. I feel that this trip into the spideyverse would be mischaracterized by being called merely ‘challenging’. I had waited a year, avoided drugs, but worked hard monitoring my thoughts, body awareness, behaviors, and ways of speaking to self and others. The spiders, I decided later, must have been fears, hatreds. Could I work with them? They were not attacking me. Could I let them live?

Regardless of whether or not you consider yourself sensitive or highly sensitive or neither, it seems that structured breathwork can replace acid trips in a number of ways. For me, my terror that I would ‘go back’ to that place showed to me / in me in Joshua Tree led me to avoid substances for months. 12 months later, I was even afraid to do holotropic breathwork, since the practice was literally developed to replicate the experience of LSD after the FDA criminalized the substance and all lab experiments on its healing properties and psychotherapeutic potentials were shut down. But I’m a sucker for gongs and for crystal singing bowls, and so I was lured into a room full of chatty hippie types, mostly white and seemingly wealthy, feathering their yoga-mat nests with blankets and pillows, chatting amongst themselves.

Once it got started, it got started. People stretched out on their mats and donned their eye masks. There was music and an invitation to breathe deeply and evenly, not aggressively or quickly, but as consistently as you could manage. No other guidance or suggestion was given, which I thought was classy. Maybe it’s living with Nu now, an adopted pantherian black kitty cat who hunts me with her slit eyes while I sleep and work and pee, that fed the first image that came to me.

The music was grounded in drumming: I was transported to the jungle. This must have been the ‘trance-inducing’ phase. It was dark and green and wet and everything was alive, glinting with gold aliveness. I was standing in a clearing, deep in rich, springy mud. Something larger glinted from inside the trees, and as I focused on it, it emerged from the darkness into the clearing with me. It was a creature – massive, a godlike size (think Princess Mononoke) – equal parts black panther and shimmering anaconda, with inky scales, feathers, claws, tails. There was something arachnoid about it, too – its movements?—its more-than-two eyes?—

It approached slowly and steadily, unfurling into the relative light of the clearing, and I felt placid and content as it flowed toward me. I knew what was about to happen, and knew that this next step was ‘right’. The creature devoured me, mostly whole; it did chew a bit, cracking the spine in a few places to help make me easier to swallow. I felt no pain, no fear, no tension. It was lovely to be taken in and up by this creaturely god. The sound of the crunching bones was a little offputting, but I wasn’t hurting; I let the ringing cracks and mushy munches wash over me as the darkness of the creature’s throat and gut enveloped me. I remember thinking, “Nice. Here we go!”

*

The cavity I entered was visionless and void. I knew that in the room where the holosonic breathwork was taking place, there was now quiet classical music playing over the speakers. I felt that the woman next to me was flailing her arms, and could hear that the one at my feet had fallen asleep, and was steadily snoring. I returned to my void and found it was the womb state. It was wonderful in there. I loved being enclosed. I floated without clarity in solid, sentient satisfaction for a few minutes, breathing bliss deeply.

Then the music changed, and with it my breathing, and with it, the movie: an interruption of our galaxy of black peace. Bright fluorescent lights were invading my chamber, and my host (my mother, I realized much later) was anxious and agitated. I sucked up the bad stuff, as had been my role for a few weeks now whenever she was feeling vulnerable. But wait—they were preparing to pull me out! I was indignant with disbelief. Who were these people? How did they not know we were not ready?

Whether it was more that the ‘breakthrough’ music was cacophonous or that my jagged breathing was chopping up the frequency, I couldn’t tell. Tremors, stress, and resistance gripped my core and sent twitches down my limbs. In the other place, I could feel myself overheating, shimmying the blankets off the yoga mat, stripping off my sweater and socks. I knew my head was thrashing, but the mind could not muster any sense of self-consciousness; this was my trip, the other people in the room were having theirs. I could not focus on anyone else anyways: harsh sets of agonizing cramps roiled my abdomen, and my muscles spasmed until it let up and they lolled. I had landed; it was over. “Untimely ripped” (Macbeth).

I was born too soon, unprepared, resentful, and worried about my mom. We both knew it was wrong how it happened, and this left its mark on us; but coming home afterward, we settled into that quiet togetherness that reestablished some sanctity and calm. I was just older and wiser, it seemed. (This ostensibly corresponded to the ‘heart music’ phase of the session, though I never confirmed that Loriel was using the five-stage sequence standardized by Grof.) This was the zero to 18-months period. Who knows what the music was doing at this point, or how long it had been. I was dreamily developing: nourished, held, and utterly adored.

But all was not well. By the time I reached a year and a half, both my parents were sad; I couldn’t understand why. When they held me, I sucked up their sadness, and they felt reassured. That’s why they loved to hold me. The happier I was, the more okay they felt. When mommy was away on business, daddy was my mommy. This worked nice, as his energy was softer, and he needed less from me. We would sit on a sloping Adirondack out in the backyard and look out at the grass and the plants in the far garden by the wall.

I remember/relive crawling across the terracotta patio and crossing the threshold onto the cool white tiles of the kitchen, moving from outside’s brilliant sunshine to cool quiet darkness inside the home. I loved feeling the slippery cool tile. I loved to hear Bailey’s nails scrape them as he approached to sniff and nuzzle his new sibling. His liver and white coat shone in the reflected sunlight through the sliding doors, and I gazed up in wonder. What a splendid, meditative animal. . .

The music wound down and cut off, and Loriel came in as a voiceover. We have reached the end of the session. . . breathe normally . . . trust that whatever came up for you was for the best. . .

Half an hour later, having wrapped up the session with some light group integration, the other volunteer and I were putting away yoga mats and meditation cushions and helping Loriel to dismantle and store her gongs, bowls, and bells. Lightly, Loriel asked how I was doing, and I knew she had noticed: at some crescendo or other, I had risen and exited the room, not returning for ten minutes. I had fled to the bathroom, almost vomited, taken some water, and then eaten multiple handfuls of nuts and seeds out of a tub someone had left in the coworking space across the hall from the main room. (I had not eaten enough before coming to the Alembic that morning, and needed grounding if I was to continue.)

I sketched some of what had happened, and she and her assistant paused in their packing and eyed me. “You had a perinatal experience?” she asked; I shrugged, and she nodded. “You’ll need to take really good care of yourself the next few days. Take a salt bath, rest, drink lots of water. Don’t schedule anything, if you can get away with that.”

*

A few nights after this journey, I remembered that Loriel was a student of Stanislav Grof’s, and downloaded one of his classic books (The Way of the Psychonaut) to scroll around in, in case something lit up to help make sense of the experience. I was waiting to find some neutral language and internal clarity before calling my mother to ask her about her experience of my birth and early years. I suddenly needed to confirm the context of the C-section.

The book is written for psychonauts (those who use psychotropic substances and/or altered states to explore consciousness) and those who would be psychotherapeutic guides (therapists whose patients work with psychotropic drugs for healing). I quickly found the section on perinatal experiences and scoured the four descriptive sections, looking for clues. There was nothing about a panther-snake-spider god, and I wondered if I had been merely absorbed into the lifeforce of the woman next to me; she had told me afterwards about her involvement in ayahuasca ceremonies, which medicine is known to produce archetypal images of serpents and jungle cats.

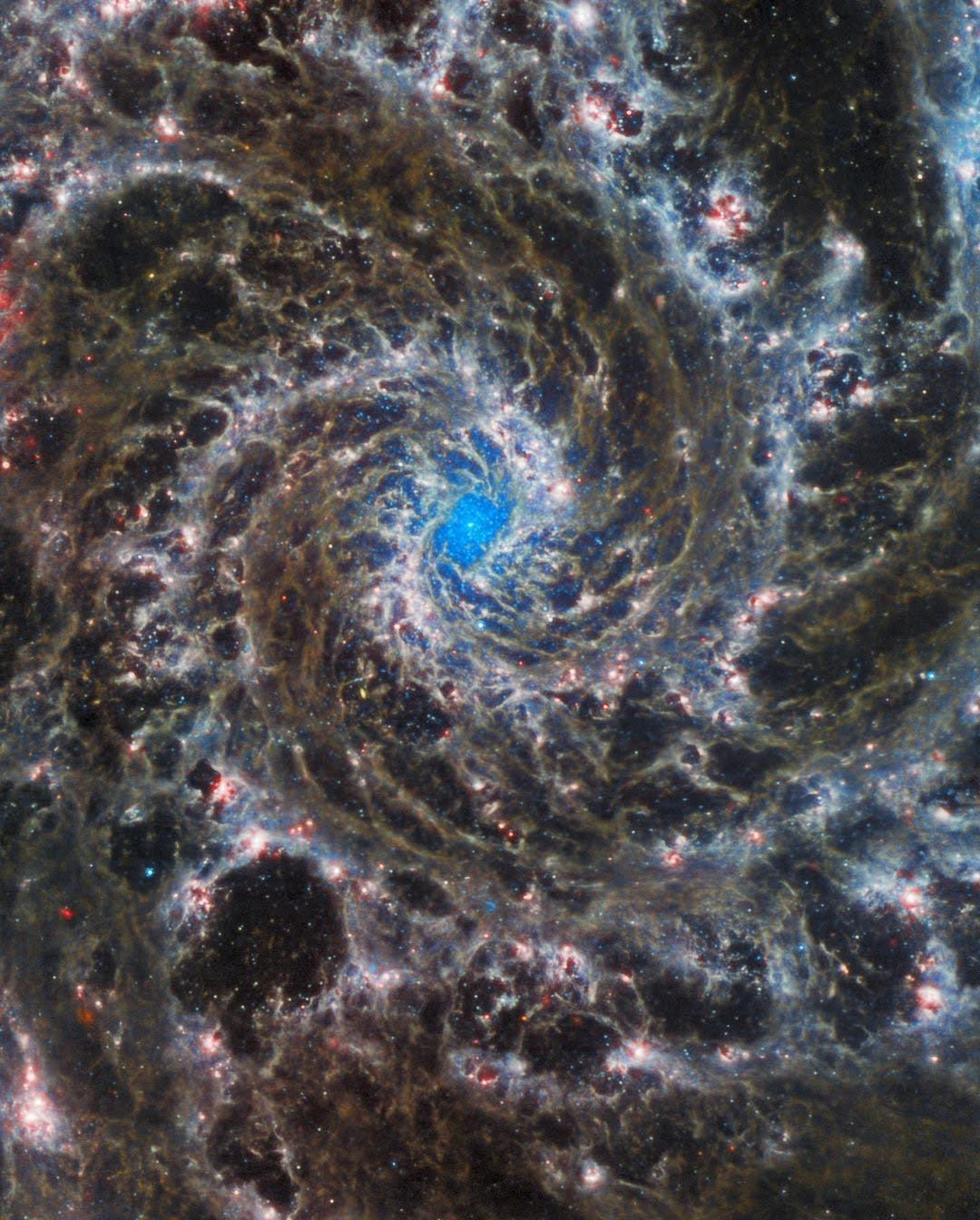

Nothing in the book seemed directly relevant to my experience. Grof writes about Freud, Alfred Adler, Otto Rank. I defaulted from research to a section of photographs to take a break, scanning amusing selfies of Stan with various visionaries: Ram Dass on Maui, Raymond Moody, the Shulgins when they were in the East Bay. Scrolling down, there followed a series of paintings, one of which had my exact spider in it.

It is a psychedelic painting by Alex Grey (“Despair,” 1996). It is a dark image (see here) depicting a seated man, his elbows wrapped around his knees, his neck bent to hide his face from the world. He’s curled up partly-fetal, in dread and sorrow, caved in on himself. The man is represented transparently, so that his organs and arteries and so on are visible; and he is besieged from all sides by various nasty creatures: snakes, rodents, scorpions, insects. Most significantly for me, there is a large spider resting on the man’s shoulder, as permanent and undeniable as the one that stayed on me in Joshua Tree for those eight-plus hours.

The caption of the painting in the Stan Grof book read as follows: Despair, a painting by visionary artist Alex Grey, inspired by psychedelic medicine. This image has classic features of BPM II—crushing no-exit atmosphere, skull, jaws, fangs, bones, snakes, and spiders.

The Austrian Otto Rank theorized that humans experience birth as a trauma that affects the rest of our lives. Stan Grof, Czech psychiatrist, delineated four distinct phases of birth, during each of which particular trauma may occur. The four stages he calls the Basic Perinatal Matrices (‘BPM’ for short). The first is the in-womb state, which can be blissful or unhappy (BPM I); the second, a state when labor has begun but the mother’s cervix has not yet opened (BPM II); the third, when we start to push out through the birth canal (BPM III); and the fourth, when we have left the womb, may involve feelings of expansiveness or of isolation and loneliness (BPM IV).

C-section babies, then, never experience the second half of the four phases of birth. The “crushing no-exit atmosphere” of a stressful onset of labor characterizes their birth trauma. I waited until the next morning before calling my mom to ask her about that day, and listened closely as she told me how she was fed a drug that was supposed to induce labor, but instead only caused painful cramping. And no wonder: it was twelve days before my due date, there was no need to rip me out and cut the cord.

She had always said she resented the doctors for coercing her into a C-section for her first delivery. Her next two children were delivered normally and were healthy, successful births. She described being nervous and being steamrolled by the ob-gyn to schedule an appointment that would suit his hospital schedule instead of waiting for the baby to come when it was time for it to come. Their reason was an alleged risk that she later researched and determined was false urgency and misinformation. This was the first time I had heard about the cramp drug, which resolved some of the mystery of my dysmenorrhea.

It was nice to be on the phone with my mom and hear her clear, confident voice narrate the experience of her first baby. I asked her a few questions about my first months and years of development, checking her anecdotal memory against the scenes from my breathwork class visions (“the movie,” John Martin would say). It all tracked, and this has helped me to trust myself in the months since then.

I’m in Joshua Tree again as I write this. It is Christmas Eve, 64 degrees and sunny. I have been unexpectedly ill since we arrived here on the solstice, purging my digestion, lymph, and excretory systems every which way in spectacular fashion. Yesterday’s new moon in Capricorn marked the end of the severest symptoms, a stabilization of the vehicle.

*

Postscript(?): “You naus-e-ate me, Mister Grinch!”

Last night the union strike vote closed, and a slim majority voted to accept the tentative agreement and end the strike. I have to imagine that my feelings of revulsion around the tactics of union leadership during this strike will not abate for a while yet, so I am going to refrain from publishing anything in-depth until that happens, if it does. No ranting about personal integrity on my part will meaningfully alleviate the repercussions of this forced hand. Suffice it to say no graduate student who is currently in or near poverty or homelessness at UC Santa Cruz (or Santa Barbara, or San Diego, or Davis, or Merced, or Riverside, or Irvine) is going to see a change in that situation within the life of this contract.

This is because the wages article cedes barely half of the money we went on strike to win—a basic cost-of-living adjustment, just like we asked for in 2019 with our COLA wildcat—and distributes it unevenly; perhaps worse, it deliberately buries certain articles like access needs for disabled workers and moves to demilitarize the campus police (who, of course, disproportionately abuse and violate homeless and mentally ill workers, a disproportionate number of whom are Black and trans). See here for more. And here.

If you want to see the Community Care article that they slashed, or want more info on the access needs, I can provide. Please keep in mind that your asking me for education and resources may be compensated with payment for that labor. This is one way we can come to trust and respect each other in ways that the UAW and the University of California may never understand or appreciate. Subscribe to Strength Reversed for a monthly fee or buy me a coffee.

UCSC was founded the same year that LSD was banned in the US. 2023 creeps over the horizon. Still a wildcat. Still resisting the UC. Determined to make peace with the spiders. More soon. . .