Tallying Surrender: John Ashbery's "The System," Meister Eckhart, and the MEQ

Adapted from a talk I gave last weekend at UC Berkeley for the Forms of Psychedelic Life: An Interdisciplinary Conference Exploring the Intersections of Religion, Ethics, Aesthetics, & Altered States

15 April 2023

The Gifford Room, Anthropology and Art Practice Building

Introduction & Context

There is an analogy between lyric poetry and psychedelics, and it has to do with the arrangement of so-called “non-ordinary” experience. In order to talk and think about this, let's say that both function on the levels of “language” and “awareness”. In poetry, we arrange language in order to rearrange awareness. In the attempt to comprehend psychedelia, our awareness is rearranged first, and any language that follows must arrange itself to reflect those changes, as much as it can. It seems however that not as many people are able to get high on poetry without lots of structural groundwork (e.g. that magical high school English teacher-turned-visionary guide); you could broadly understand poetry as a kind of a psychedelic medium for linguistically-sensitive order freaks.

The apparent differences between a lyric trip and a psychedelic one are more a question of accessibility on the pre-linguistic cognitive and sensual planes, and a matter of relative exploitability: poetry is more immune, though not totally, to the zombification of biomedical-industrialized capital. They haven’t synthesized a lyric poem pill—yet.

In individual instances where a person turns to either drugs or poetry for comfort, guidance, self-exploration, or spiritually-inflected clarity, both categories say, in some form or other, as Rilke said, Du musst dein Leben ändern: “you must change your life”. Surrender is the first step and maybe the only serious prerequisite for a transformative journey with either of these mind-altering substances (and I do argue that lyric is a substance!). According to the ways that both have been or are being operationalized by universities , e.g., and their stakeholders, both are tools for training focus and developing the capacity for sustaining deeper states of attentiveness; and both offer the fashionable seduction of “healing.”

My professional research interest in poetry lies in its inherent religiosity and in its application for pedagogy. In a classroom or workshop context, surrender, our prerequisite, assumes in the student the basic willingness not to understand, at least not right away, and courage and wherewithal to be curious amidst that self-conscious state of confusion. When reading a poem, patience, humility, receptivity, and attention to breath all ground you when lost, resistant, or afraid. The poem arranges language, with degrees of non-ordinariness, and the reader correspondingly rearranges her awareness to accommodate this weirdness. In this vein, John Ashbery is an exemplary guide: tactful, well-paced, and unrelenting.

ASIDE: Ashbery’s prose poetry is comparable to a Kilindi-level, 9-gram psilocybin journey… if you’re new to poetry, get in touch with me and we can match you with a more suitable teacher. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend John Ashbery’s prose poetry for your “first trip”, though you could try his first book, which usually appears to make mainstream sense more convincingly than any of the 30 that follow. By the way, preferring one poet or style of poetry over another is natural, like with gravitation for cultural, religious, or intuitive reasons toward a certain category of psychedelic or species of psilocybin. It’s my own conviction that everyone should do a serious dose of poetry at least once, and I’m happy to help draw up personalized readers, if that’s interesting to anyone, reach out and let’s work together.]

Ashbery & Modern Medieval Mysticism

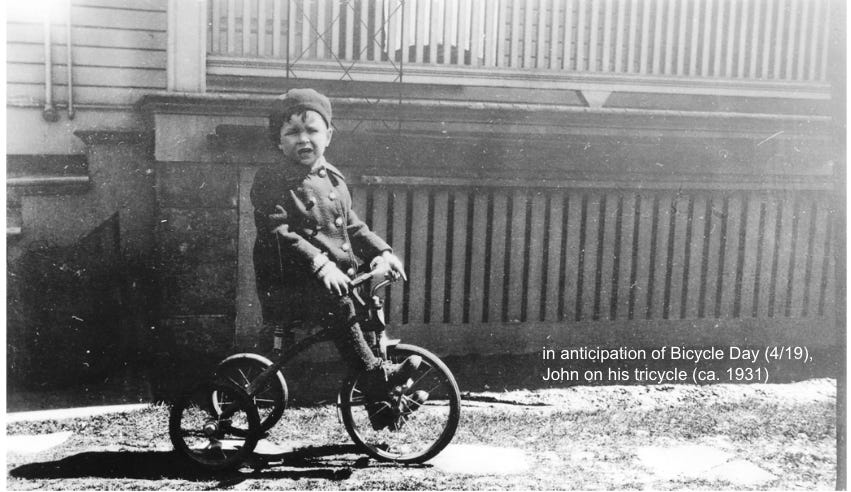

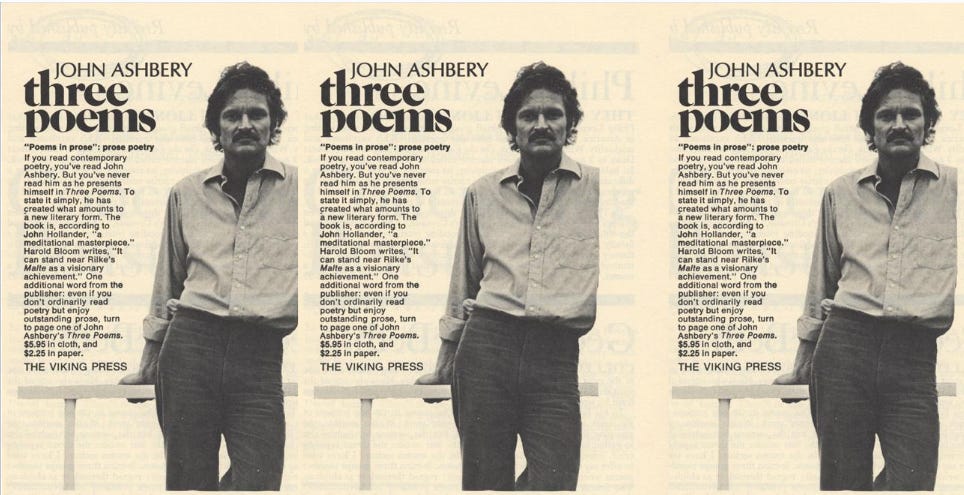

John Ashbery was born in 1927 on a farm in upstate New York, and lived most of his younger life in New York City, later teaching creative writing upstate at Bard College. He was agnostic himself, avoiding any explicit religious topics or images in the bulk of his books. Despite peppering Three Poems with allusions to Tarot and astrology, in a 1974 interview, he repudiated any trendy interest in the occult by observing, “The occult is not mysterious enough.” (Poet’s Craft) Nevertheless, for some reason his poems have always put me in mind of the mystical medieval Christianity that bloomed in Europe, especially in Germany, in the late Middle Ages, exemplified by the radical preaching of Meister Eckhart. The mystical strains of Catholicism then were developed by thinkers in and of the church, in the form of individuals or small communities challenging the institution from within, and this is also how I see the incredibly successful yet slippery Ashbery in the realm of the Modernn American poetic ecosystem.

Particularly in his book of 1972 prose poetry, Three Poems, the quality of voice, tone, and style that seeps out of Ashbery puts me in mind of Meister Eckhart, whose informal, charming, and arresting sermons emphasized the individual layperson’s felt union with God, to the exclusion of and even in direct opposition to any institutional loyalty or clerical hierarchism. What we think we understand today as “mysticism,” a word coined in 19th-century France and so general as to be unhelpful, has its roots in this Western European medieval Catholic theology, of which Eckhart is arguably the high point of the German tide.

Dominated by the Eurochristian frame exemplified by Eckhart, most of the 19th and 20th-century writing on “mysticism per se” has fallen to the same criticism that took down Walter Stace, a public philosopher and epistemologist whose popular mid-century books on the subject have since been vetoed by the social constructivists—and rightly so—for their cringey perennialist syncretism. Stace developed the original Mystical Experience Questionnaire, which a Theology graduate student, Walter Panhke, modified in 1962 for the famous “Marsh Chapel Experiment” experiment at Harvard.

The MEQ has been tested, challenged, verified by factor analysis, retested, castigated, etc. since it was first filled out by Theology students, 90% of whom reported having a mystical experience on LSD.

How do we standardize something we don’t understand? The criticism of the Walters’ sense of the mystical, as used in this experiment, is that it’s conceptual, not empirical, and that this forbids workable science. Walter Stace wrote that he developed his list of common dimensions of mysticism—undifferentiated unity, dissolution of self, feeling of revelation or veracity—out of the Upanishads. We can get into what’s messed up about that later. He identifies mysticism as the “realization that the personal self is identical with the infinite self.”

Consider this quotation from Ashbery in that aforementioned interview, given while he was finishing Three Poems (Poet’s Craft 84):

In an attempt to consider current “humanist”, “transpersonal,” and “respiritualized” potentials of psychedelic experience, I thought that using the analogy of the MEQ would provide for nonpoets and less literary types a provocative way into the demanding, oblique, and materially unrewarding arena of poetic interpretation. Perhaps it will prove to be a bad map for good territory, but at least it gets us on the same wavelength. Ashbery’s poetry is notoriously “difficult”—the darling of stuffy postmodernist critics for all the wrong reasons, in my opinion—and yet he repeatedly said in interviews that the goal of his poetry was always to open and deepen communication with his readers, and furthermore, that one could accurately read all of his poems as love poems. In addition to reading his prose poem “The System” as a love poem, however, I have found it generative to read it as both trip and trip report, experiment and analysis, an experience and evaluation of the ways in which a “non-ordinary” state (like reading a poem or being in love) rearranges awareness in and through language.

A bit of humanist context here: The contextualizing narrative of trauma and trauma healing dominates the mental-health/”legalize it” angle of the “psychedelic renaissance” and has also gained a lot of ground recently in cultural studies and literary studies, possibly in response to the accelerated collapse of the institutional humanities as a viable place to work and think. It is the perceived disconnection between the bounded separate self and other that causes the emotional and mental trauma that is the site of the origins of the Western love lyric.

The Other, first in the case of prayer, was God; the troubadours thru the romantics transferred their longing for union with this separate otherness onto a mortal beloved. Love lyric and pop music are modern correlates here. In both religious and “secularized” cases, apostrophe -- an exclamatory figure of speech, an individual's address or supplication -- captures what we moderns interpret as a bid for "mystically" unifying connection across space and time. In attempting to define its genre of study, lyric theory often focuses on two complementary features of the language of the lyric poem: its manipulation of time into timelessness; and its uniquely intimate, relational quality.

In secular postmodern poetry (JA for instance), the target interlocutor is not usually divinity nor even love object, but more often the longed-for reader. This cognitive and felt imposition of dualism (self to other) addressed by lyric is precisely what many report being dissolved, and sometimes later resolved, through the use of psychedelics. This dissolution is also the goal of Christian contemplative practice as developed in the medieval church and formally enacted in Meister Eckhart’s sermons. And the MEQ, of course, claims to measure such a unifying dissolution in a standardized way.

My observation is that this (dissolution of boundaries, building up and exploding of self, transformation of awareness of interrelatedness with others that psychedelics occasion) is what certain lyric poems have always been doing, albeit with subtler neurophysiological fireworks. The wellness-industrial complex’s marriage to pharma-capitalism, embodied in the MEQ, and traditional Ivory-Tower literary criticism both seek to impose rational order, the latter often projecting ideological sensemaking of traditional social science where there is none. Today, instead of coaxing a close reading, I want us just to read the first part of a poem together instead.

As an aside: Criticism as the mainstream practices it is a defensive operation. If the academy is truly going to assimilate wisdom from psychedelic experience, this is going to have to 180 – to flip from defense to surrender (to what? We’ll have to work together to figure that out). At this point, based on where I see us headed, I orient my critical gaze toward the abolition of the university business model as it exists in the United States. I understand abolitionism, of prisons first, inherent to any ethical psychedelia. Although they do not take it this far, I cite The Undercommons (Fred Moten, also of the UC system, and Stefano Harvey) as an important underlying theoretical source here.

“The System”

Ashbery’s 1973 book Three Poems is a product of the 60s. According to one of his best readers, Cal English professor John Shoptaw, the man who introduced me to Ashbery when I was a freshman here, we can read “The System” as “a religious history of the sixties and a sermon on living out one’s unknowable destiny” (Shoptaw 135). The dominant voice, or the persona of his wandering lyric “I”, is that of a cultural historian. “‘The System’ begins with a history of the ‘love generation,’ not only in its suburban Zen or Jesus ‘freaks,’ but the countercultural movement as a whole, with the benchmark names, dates, and places omitted as usual.” (Shoptaw 148)

Ashbery’s careful shredding of the expectations of relationship dynamics ground the poem both as devotional love letter and work of philosophy. One salient biographical detail is his meeting David Kermani: Ashbery met and fell in love with the person who would become his lifelong partner while he was in the middle of composing Three Poems, and he credits this with influencing the book (136). He also started going to therapy for treatment for depression shortly before beginning writing.

Conclusion

It is the work of the close readings in the first chapter of my dissertation to try to persuade more specifically about the particular connections I see between this poem, Meister Eckhart, and the psychedelic states of consciousness as the MEQ and others have tried to understand them. With these comparisons, I argue for the centrality of psychedelic forms of spirituality in a reinvigorated ‘postsecular’ understanding of the lyric genre, as well as for the centrality of the lyric genre in a revitalized artistic education.

I said at the beginning that Surrender is the first step and maybe the only serious prerequisite for a transformative journey with either poetry or psychedelics, and I gestured to the fact that both have been or are being operationalized by universities as tools for training focus and for creating, or recreating, humane subjects out of students.

In my own research and my own pedagogy, I understand the practice and experience of art to be one mode of integration of lived experience, just as I understand Academia to be integration for that Art. In that sense, literary theory is attempted integration of poetry. Like criticism, I find psychedelia potent when it is self-undermining: in the case of John Ashbery, we see a deliberate dissolution of genre and of the lyric “I” into the prose poem form; if you go home and read the rest, you can enjoy “The System” breaking down, and you may in turn break down “The System.” Maybe you’ll even get to have your own breakdown ;)

Depending on the mind and the circumstances, you can get pretty far out with Ashbery’s prose poems and many other Modernist and Postmodernist lyric forms; I think the desire to reach beyond the limits of legibility and language itself that is so prevalent in 20th-century literature prophesied the 21st-century return of self-transforming drugs to the mainstream of even institutional (university) consciousness. Regardless of their apparent centralization in any era, however, there are always people and texts at the limits of awareness and of language, and these are often hidden in plain sight. Surrender is the acknowledgment of such limits. Reading the lyric offers one method of embodied transcendence of these limits.

Thank you for your time!

For a full list of speakers and titles of presentations, see here.